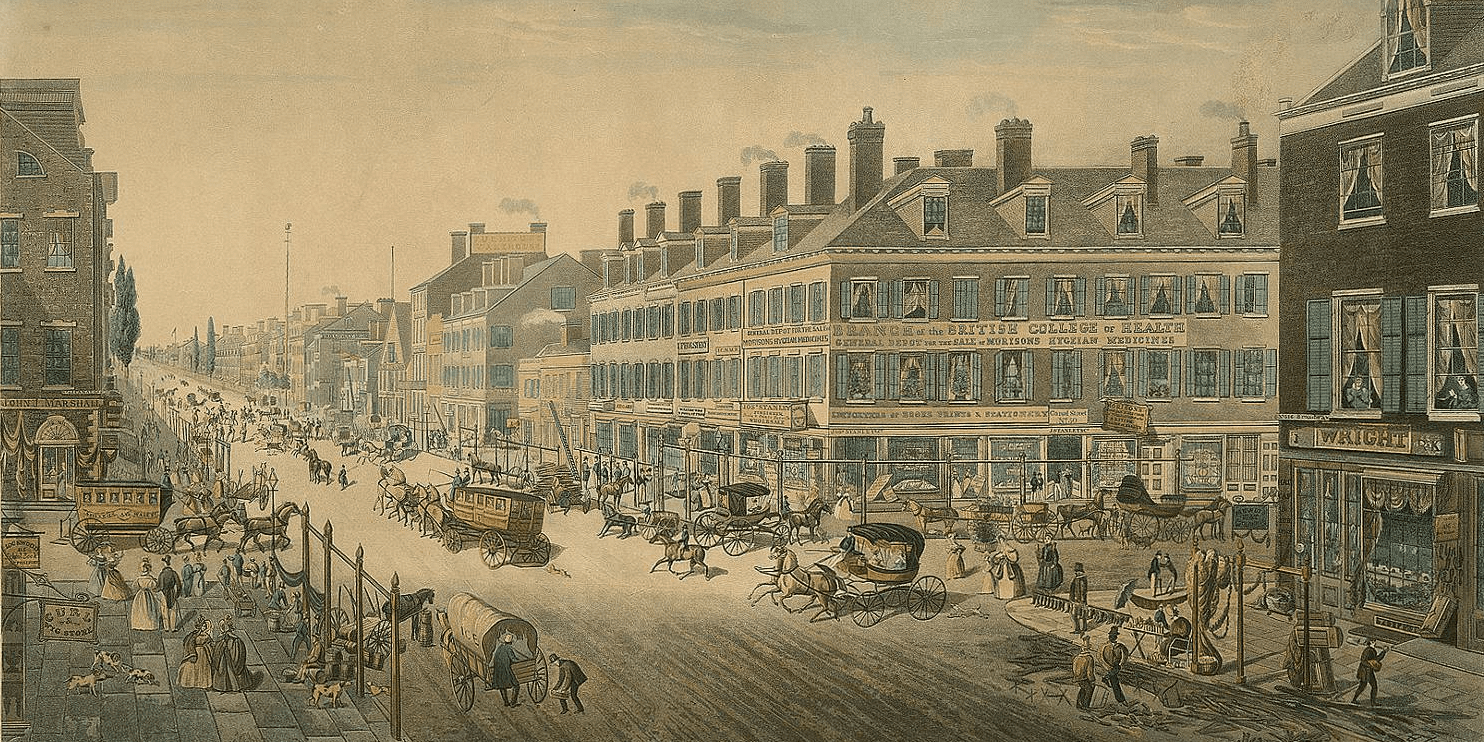

Modern New York City boasts a vast array of markets selling everything from household goods to groceries and much more. Residents flock to them because they’re consistently clean, well-organized, filled with pleasant aromas, and offer goods at affordable prices. In old New York, however, the situation was drastically different. The system of public markets was just beginning to take shape, according to manhattan1.one.

Manhattan’s First Popular Markets

In 1786, at the request of influential residents from the then-remote Catherine Street area of New York, the city’s legislative body—known then as the Common Council—approved the construction of the Catherine Market. As was customary, interested parties provided the land and covered the initial construction costs. In the following decades, a mix of local and municipal funds was used to expand the facilities. This blend of grassroots initiative and government response led to a highly successful public market that became a community hub and a vital food source for the working-class neighborhood.

By the late 1810s, Catherine Market, located in Lower Manhattan east of the present-day Brooklyn Bridge, had become one of the city’s wealthiest centers for fresh produce. Its 47 butchers, over 25 fishmongers, 60 permanent farmers, and dozens of street vendors, along with numerous grocers, supplied roughly 25,000 people with food. Depending on the season and day of the week, the market drew between 2,000 and 5,000 shoppers daily.

Catherine Market soon became part of a strictly regulated system where fresh goods, particularly meat, could only be sold in markets owned and operated by the municipality. As the population surged from 30,000 to 160,000 between 1790 and 1825, the city responded by expanding the system from six to eleven district markets.

The Rise of Gansevoort Market

Another important food market was established in the Gansevoort Historic District during the 19th century. Its location on the Hudson River waterfront was ideal for receiving meat, dairy, and vegetables shipped in by boat. Following the Civil War, the market expanded to encompass Skelly & Fogarty’s Centennial Brewery on 14th Street. Vendors selling regional produce also actively conducted business there. In 1893, the New York Biscuit Company, which later became Nabisco, added to the food-related businesses clustered around the market. One can only imagine the streets filled with the combined aromas of manure and fresh cookies!

The Gansevoort Market was always a multipurpose space. Low, Italianate-style buildings stood alongside tall warehouses. Some of the iron sheds built to transport meat into these warehouses have survived to this day. The nearby Hudson River Railroad freight yards allowed for the transit of meat and other foodstuffs further uptown and off Manhattan. Starting in 1869, Cornelius Vanderbilt owned the rail line along with the New York Central and expanded the network to connect with meatpacking plants in Chicago.

By 1880, New York’s market facilities were in decline, and the vendors spilling onto the streets began to obstruct pedestrians and horse-drawn carts. The city authorities decided to create a new commercial hub in the Gansevoort area. Though initially intended for fruits and vegetables, the Gansevoort Market eventually became a meat market. Horses transported most of the produce from the piers, and buyers brought huge carts to the market, causing traffic jams. By 1900, nearly 170,000 horses crowded the streets of Manhattan. Over 250 slaughterhouses and meatpacking companies filled the Gansevoort Market area, intensifying the odor and the amount of manure.

A Well-Designed Market Model and Its Development

New York’s market infrastructure represented a sophisticated, spatially organised system. Its facilities spanned all districts, ensuring convenient access to goods for every resident. This was crucial for an efficient food distribution system, as New Yorkers, without refrigeration, had to shop up to twice a week in winter and up to six times a week during the hot summer months.

The collaboration between vendors, shoppers, and municipal officials ensured that the volume of trade matched the population size of their districts, indicating a high level of supply and demand. Overall, the public market model in old New York was responsive to local demands for opening new markets or upgrading existing ones, and it was inexpensive. Through the implementation of fees, rents, and excises, the system was largely self-funding.

As Lower Manhattan’s population grew between 1790 and 1825, the public markets expanded in both size and location to fully meet the needs of New Yorkers. Regardless of where a person lived, a market was within a 10-minute walk, a critical factor in organizing an effective food distribution system in a rapidly developing urban center.

Crucially, the city’s market system served as the primary defence line for food quality. It ensured the safety of the supply by punishing those who sold rotten and spoiled goods. Furthermore, it established standards of cleanliness in daily food handling and sales practices. For example, market clerks appointed by the city ensured adherence to quality standards and fair trade principles at every location. With a large number of independent vendors, public markets allowed shoppers to compare prices and quality. Vendors also kept pressure on their peers, working with market clerks to penalise wrongdoers and maintain their market’s reputation. Moreover, butchers—the city’s most elite food suppliers—were craftsmen who handled their important perishable goods skilfully and carefully, ensuring high-quality products. Finally, through strict licensing policies and frequent purchases, street markets fostered repeat business and reinforced trust between buyers and sellers.

Beyond protecting public health, the market system laid the groundwork for equal access to food. Whether New Yorkers lived in the wealthier central districts or the poorer outskirts, they sourced food for their households under the same institutional conditions. This continued even as the city expanded. The development of a new district was contingent on the expansion of this municipal service, which was partially financed by revenues from the larger, centrally located markets.

Market Operations and Early Innovations

The system was also effective in preventing waste. Markets operated six days a week, from early morning until late evening; only fish stalls were open on Sundays. Before the advent of refrigeration, perishability was the main constraint. Therefore, vendors—including butchers and fishmongers who attended markets daily, and farmers from rural New York who came less frequently—brought only as much stock as they expected to sell that same day.

The sale of choice goods began early in the morning. By 9 AM, the main market trading was finished. Poorer shoppers then arrived to buy cheaper, less popular goods. At noon, resellers joined the trade, picking up the remaining stock and selling it at discounted prices after the market closed and on nearby streets. Waste from the main trade, such as leftover butchering scraps, was processed within the city’s “nuisance economy” by tanneries and manufacturers of soap, grease, and glue.

The Manhattan Refrigeration Company was founded in 1894 and managed nine refrigerated warehouses. By 1906, a network of underground pipes connected the cooled warehouses, providing storage for perishable goods delivered by steamships docked near the Chelsea and Gansevoort piers. Mechanical refrigeration was a new invention at the time that helped make the market a center for food distribution businesses.

Much like modern intelligent systems, the success of old New York’s market system hinged on information exchange between key groups. The core of the matter was a democratic process of petitioning and negotiation. Residents, vendors, and city officials had to constantly agree on the location, size, layout, building materials, major rules, and day-to-day practices of the public markets. This process facilitated communication between the interests of the neighborhood residents and city policy. Even with a complex political landscape, the system worked because it was participatory, decentralized, and coordinated.